Sitār Ang 1982 -2023

reMix – reMastered Version Series Vol.12.

audio & ordering:

https://amarxe.bandcamp.com/album/sit-r-ang-i-ii-1982-2013-re-mix-mastered-version-series-vol-12

https://youtu.be/qYE8bV5kYWw

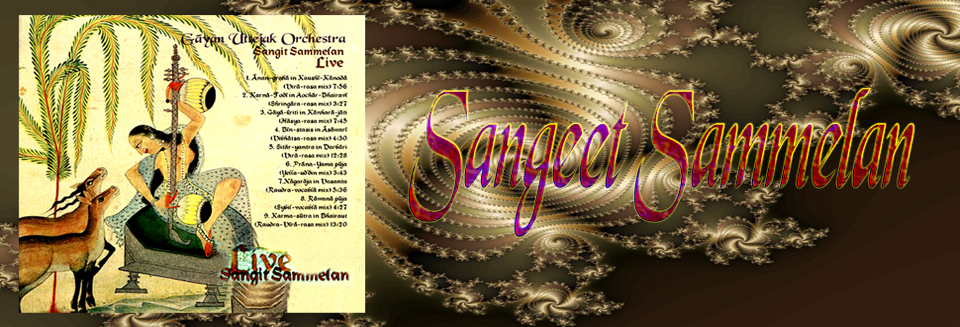

CD-01

01_Faiyazkhāni Bhairavī_(1982_Live) 13:19

02_Hortobhai_(2011) 07:00

03_Dubahār Kriti_(2013) 09:43

04_Barokhāni Gat_(1992) 10:55

05_Darbahāri_(2011) 07:08

06_Darborea_(2006_Barā) 25:41

CD-02

01_Surbahāri Tūlpa_(2013) 08:39

02_Shankānanda_(2006) 04:47

03_Yinborea_(2006_Barā) 18:25

04_Horto-ki Todī_(2013_Live) 10:42

05_Darborea_(2006_Chotā) 20:23

06_Inneralius_(2012) 09:45

The Sitār Ang cover image is based on the cover of the first Sitār lecture book of eL-Hortobāgyi, published by Sangeet Karyalaya in 1943.

The small book was written by Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit (1893-1989)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krishnarao_Shankar_Pandit#Biography

https://www.guo.hu/___WORDPRESS/Laszlo-Hortobagyi_Gayan-Uttejak-Orchestra/_By_The_Way/Sangeet/1953_My first Sitar-booklet.pdf

and which, of course, could only be used with the knowledge of a few specific ‘secrets’ of sitār technique that could only be learned through practical instruction.

Despite northern India’s population of hundreds of millions and its centuries-old classical music culture, Hindusthān‘s ONLY classical music publisher was the Sangeet Karyalaya of Hathras, founded by Prabhulal Garg (Kaka Hathrasi) in 1935 and publishing the long-established Sangeet magazine.

Lakshmīnārāyan Garg, Kaka’s son and the chief editor of the magazine, (passed away at age 88.) and the leader of Sangeet Karyalaya, known as Garg and Co. in its early life, has done more than just publish Sangeet.

Next door was the KCCCO instrument manufacture. (Temple Road). My first sitār was made there and in the sixties I managed to order all the issues and books of the Sangeet periodicals that were published up to that time (and later too).

The following extract illustrates the spirit of Sangeet :

In 1937, ‘Sangeet Bhushan’ Lakshmiprasād Mishra wrote of his chance encounter in Varanasi (Benares) with Vishnu Digambar Paluskār, the grand old man of Hindusthāni music tradition.

On why rāga-s no longer work miracles as legends claims, V.D. Paluskār harrumphs about making money out of music:

” in an epoch when music is no longer a purely spiritual pursuit, what hope is there of it wresting a miracle? ” – he retorts.

More on:

https://scroll.in/magazine/1008254/after-an-unbroken-run-of-87-years-indias-oldest-classical-music-magazine-is-facing-a-bleak-future

*

Here reable an extremely symplified outline of the history of the traditional practice of the sitār instrument. Two historical trends (bāj) , the Gāyaki and the Tantrakari, can be highlighted to depict the musical background of the Sitār Ang on this two CDs.

In contrast to Western classical music practice, where the participating musical heroes neutralise and robotise as much of their individual personalities as possible in order to achieve harmony, in Indian society, which appears homogeneous, musical styles can be described in terms of the musical schools and trends founded by great personalities, and yet this is how they have become a unified musical vernacular on a continental scale, transcending caste boundaries.

It is therefore necessary, for example, to present the certain instrumental musical movements through their outstanding representatives.

The Indian continental network of guru-shishyā-shagīrd elite (inbreeding) relations of representatives without caste preferences is similar to the network of European ruling families covering the whole of Europe in the 19th century.

Gāyaki Ang and the Merukhand system

The Progenitor:

Ustād Amīr Ali Khān (1912-1974) was born at Akole (Mahārashtra), and brought up in Indore, where his father, Shahmīr Khān served the princely court as a sārangi player. Young Amīr Ali began his training in vocalism and the sārangi at an early age.

For young Amīr Ali’s training, his father once sought the documentation of the merukhand discipline from a colleague at the Indore court, Ustād Nasīruddin Dāgar. The Ustād refused on the grounds that such knowledge was not available to “the son of a mere sārangi player”. The remark stung Shahmīr Khān, and he developed his own method for training Amīr Ali in the merukhand system.

The merukhand discipline (meru = mountain, khand = fragment) is a logically sequenced compendium of all the 5040 (7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1) melodic patterns that can be generated from seven notes. The patterns are sequenced according to a particular logic, and required to be practiced endlessly until they get “programmed” into the ideation process of the musician. The mastery of these patterns also, obviously, developed the musician’s technical ability to execute the most complicated melodic passages. When performing a rāga, the musician chooses the patterns compatible with rāga grammar for exploring the melodic personality of the rāga. (Dīpak Rāja)

Performances in the Indore gharānā are noted by the style of Abdul Wahid Khān, and the tāna-s reminiscent of Rājab Ali Khān. The merukhand structure is similar to that practiced by Aman Ali Khān of the Bhendibazār. The khyāl gāyaki in the Indore gharānā retains the slow development and restraint from frills as in the dhrūpad Amīr Khān‘s music was an introverted, dignified ‘darbār‘ style.

The Indore Gharānā’s ramifications

01= Indore Bīnkāri Bāj

Bande Ali Khān Indore Bīnkār (1830 – 1896) was the son of Ghulām Zakīr Khān of the Saharānpur, contemporary of Sādiq Ali Khān of Jaipur (1893 -1964) . His sister was married to Behram Khān Dāgar.

His disciple was Abdul Wahid Khān of Kirānā.

02= Mewāti Gharānā

Ghagge Nazir Khān and Wahid Khān are regarded as fountainheads of the Mewāti gharānā.They were descendants of the Qawwal Bacchon gharānā.

Raīs Khān (1939 – 2017) belonged to the Mewāti gharānā (classical music lineage) which is connected to Indore gharānā and the “bīnkār bāj gāyaki ang” combined with rūdra vīnā approaches carried out by Raīs Khān‘s father Mohammed Khān, a rūdra vīnā player and a sitār-ist. Belonging to the Mewāti gharānā which goes back to the Mughal period, it produced famous singers Hassu Khān (died 1859) and Haddu Khān (died 1875) from the school of Bāde Ināyat Hussain Khān (1837-1923)” (He was the first person who introduce bol-bant technic in Khyāl Gāyaki.

03 = Etawah Gāyaki Ang

Sarojān Singh of this gharānā was an invited singer of Mughal Darbār in Delhi. His son Turab Khān (previously known as Baddu Singh) and grand-son Sahabdād Khān (previously known as Saheb Singh) were also shagīrd of Nirmāl Shah Bīnkār of Seniā, Sahabdād Khān was brother in law of great vocalist Ustād Haddu Khān of Gwālior gharānā and also learnt vocal music from him. He applied his music on vocal music and sārangi. Afterwards he started to play sitār and he was the inventor of the instrument surbahār.

He lived in Etawah, near Agra (hence the name of his gharānā as Etawah) where he was a musician in Naugaon Darbār. He had two sons, the elder Imdād Khān (1858-1920) and the younger Karimdād Khān.

Imdād Khān lineage: Enayat Khān (1894-1938), Vilāyat Khān (1927-2004) and their family: Wahid Khān (?), and disciples : Shāhid Parvez (1954-), Budhaditya Mukherjī (1955),etc.

Seniā – Maihar Gharānā

The musicians belonging to the gharānā follow the strictest performance of the basic ālāp-jhōr-jhāllā parts of a traditional dhrūpad rāga. These movements are always performed without rhythm accompaniment. During the performance of the jhōr, tempo changes are used to separate the movements and a short rhythmic figure marks the end of the section, so the rhythmic figures within the jhōr have structural significance. This phrase-closing motif also appears in all non-Seniā jhōr performances. Sometimes, the basic jhōr movements are usually followed by a khyāl style vilambit gat with tāna improvisations, and the performance concludes with a jhāllā structure performed in a tāla period.

From the mid-1930s in Maihar (U. P), the emergence of a special style of music – Bīnkāri Bāj – represented by Ustād Allāuddin Khān and within India at that time, which, although it has its source in the Mughal court music of the 14oo-s, Seniā gharānā, represents a so kind abstract small instrumental style within the inherently vocal Indian musical ocean, not at all characteristic of the music of the great Hindusthāni past.

The style is thus characterised by a code system of (matrix) sets derived from centuries of standardisation of rhythmic-mathematical constructions – more easily monkeyed with by white men -, by the poverty of melodic variations and their modal polyrhythms, and by the cool – sometimes bleak in the performances of successors – distance from the human-ecstatic factor of singability.

In contrast with the merukhandi concept, where the elaborate (aroha-avāroha) pyramidal matrix constructions of separate rāga scales and the improvisational tāna-sargam-bol-bant sets of associations that have become blood concentrate on the most characteristic character (rasa) that follows from the sound sequence of the respective rāga-s, untill then the Seniā-Maihar system superimposes the hundreds of the accumulated and rehearsed rhythmic patterns upon the rāga sound sequences.

Abdul Wahid Khān practiced Todī and Darbāri day in and day out. When asked why he limited himself to only two rāga-s, his response was that he would have dropped the second one also if morning time could last forever. One lifetime, according to him, was not enough to do justice to any rāga. He was forced to change from Todī to something else only because of the setting sun and the gathering darkness.

The Seniā gharānā dates back to the golden age of Akbār Emperor Mughal court music, when the first instrumental compositions would try to reproduce multitude of vocal pieces of that time, on their instruments (rūdra-bīn, surshringār, sarod, rebāb,etc.).

This is how classical music, originally sung like an instrument, appears as an unsingable abstract instrumental style in the sea of medieval Hindusthāni vocal music.

The best known representative of Seniā gharānā is Pt. Ravi Shankar (1920-2012), this is how the ‘white man‘s last encounter with North Indian music came about, when from the second half of the 1950s onwards, this minority, albeit genius trend of Indian music, was identified from John Cage to Yehudi Menuhin to the Beatles as the whole Indian music culture in the West.

Nowadays:

Amazing homogeneity, all incoming pigment-rich trends are quickly reduced to the jazzoid-Gershwinian soundscape of the major-minor system, including most of the repetitive (minimal) school. The self-serving onanism of jazz, which leads nowhere, has been confused with the centuries-old improvisational practice of the high cultured Eastern music, even though the two are heaven and earth. This horrific and distorted practice continues today, with ever more horrifying amounts of kitsch.

This astonishing contemporary music-historical bankruptcy can be clearly seen in the hyped to death Whiplash (2014), where the humanism of the fist of the American brutal “aesthetic” dictatorship is radiated on to the adust cerebellum of mortals, where the quantity of sounds masturbated per second legitimizes the musical talent.

*

Since being a part of a tradition is possible only by being born into it, this also means that it is never possible to leave it. A disintegrating social fabric loses its cultural cohesiveness and therefore the jealously guarded intellectual vaults, technical secrets and legacies of family genealogies born into previously closed schools live on as family heraldic shield. However, their importance in the transmission of musical heritage is diminishing and homogenising into the genre standards of the so-called music industry market.

It is very pity to see how, in this final Sonderangebot, the great Ustād-s and Pandit-s who could afford to cling to their unique but fading family traditions become the knights of the saliva and the servants of the manipulated tastes of the global music industry.

*

With this in mind, it did not even occur to me to ape these traditions as an external person, but I tried to combine the colloquial practices of that baroque music, which had died out in Europe, with the practices of the local musical colloquial that still existed in the so-called Eastern hemisphere of the world.

All of this requires the knowledge to combine the European system, once a minority in the world’s musical culture and globalising the world standard of welltempered scales, with the unique traditions of Asian musical thought, which is in the process of disappearing.

The last living (but dying) colloquial-vernacular musical language now can only be found in the Arabian-Indian World on this planet.

Though the extinction of the traditional Indian schools (gharānā) had already commenced in parallel with the disappearance of the mahārāja courts (after 1947) and the general misunderstanding of the classical Indian music by ”white man’s” consumption could also lead to the development of a consumable Indian music that was comparable with the global “conform-idiomatism” of the awful pop-New Age industry and finally died out about on the symbolical day of Ustād Vilāyat Khān‘s death (March 13, 2004).

The Indian and the World Music today it has become a Tāntric rectum cleaning and the silly 4/4 groove loop music of entertainment industry characterized by kitschyworld and wellness-ambient facility that will operate as one of the Wellness-Neuronetics subdivisions of Wychi-Exonybm Corporation.

(Lāszlō Hortobāgyi-Hortator, 2013)

*

A Sitār Ang Cover képe a Sangeet Karyalaya által 1949-ben kiadott eL-Hortobāgyi első Sitār tankönyv borítójának a felhasználásával készült.

A kisméretű könyvet Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit (1893–1989) írta:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krishnarao_Shankar_Pandit#Biography

https://www.guo.hu/___WORDPRESS/Laszlo-Hortobagyi_Gayan-Uttejak-Orchestra/_By_The_Way/Sangeet/1953_My first Sitar-booklet.pdf

s amely természetesen csak a néhány speciális, kizárólag gyakorlati útmutatás révén elsajátitható sitār-technikai ‘titkok’ ismeretének a birtokában volt használható.

Észak-India többszáz milliós népessége és a többszáz éves klasszikus zenei kultúrája ellenére is, Hindusthān-ban EGYETLEN klasszikus zeneműkiadó létezett a hathras-i Sangeet Karyalaya, amelyet Prabhulal Garg (Kaka Hathrasi) alapította 1935-ben és a nagymúltú Sangeet folyóiratot adta ki.

Lakshmīnārāyan Garg, Kaka fia, a folyóirat főszerkesztője volt, (88 éves korában hunyt el.) Korai életében Garg és Társa néven ismert Sangeet Karyalaya intézmény vezetője azonban többet tett a Sangeet zene magazin kiadásánál.

Mellette müködött a KCCCO hangszer manufaktúra (Templom Road.). Első sitār-omat is itt készítették és a hatvanas években még sikerült megrendelnem az addig kiadott Sangeet periodika addig (majd késöbb is) elérhető összes számait és könyveit.

A Sangeet szellemiségét az alábbi részlet ábrázolja:

1937-ben a “Sangeet Bhushan” Lakshmīprasād Mishra arról írt, hogy Varanasi-ban (Benares) véletlenül találkozott Vishnu Digambar Paluskār-ral, a hindusthān-i zenei hagyomány nagy öregjével.

Arra a kérdésre, hogy a rāga-k miért nem tesznek többé csodát, ahogy azt a legendák állítják, V.D. Paluskār a zenéből való pénzcsinálással kapcsolatban morgolódik:

“egy olyan korban, amikor a zene már nem tisztán spirituális tevékenység, milyen remény van arra, hogy csodát csikarjunk ki belőle ” – vág vissza.

https://scroll.in/magazine/1008254/after-an-unbroken-run-of-87-years-indias-oldest-classical-music-magazine-is-facing-a-bleak-future

Itt rendkívül szimplifikáltan jelezve a Sitār Ang két CD-jének zenei hátterét ábrázolva, két történelmi irányzat, (bāj), a Gāyaki és a Tantrakari, emelhető ki a sitār-surbahār hangszerek tradicionális gyakorlatának históriájából.

Szemben a nyugati klasszikus zenei gyakorlattal, ahol a részvevő zenészhéroszok indivuális személyiségük minél nagyobb részét semlegesítik és robotizálják a zenekari összhang érdekében, úgy a világnézetileg homogén szubjektumokból álló indiai társadalomakban a zenei stilusok a nagy egyéniségek által alapított zenei iskolák és stílusok révén írhatók le, és mégis ezáltal váltak kontinens méretü , a kaszthatárokat felülíró egységes zenei köznyelvvé.

Ezért szükségszerű például az egyes hangszeres zenei irányzatokat a kiemelkedő képviselőiken keresztül bemutatni.

A kasztpreferenciáktól mentes képviselők tanitvány-mester elit (beltenyészeti) kapcsolati hálózata hasonlatos az európai uralkodócsaládok teljes Európát lefedő hálózatához a 19.századra kialakulóban.

Gāyaki Ang és a Merukhand rendszer

Az alapító:

Ustād Amīr Ali Khān (1912-1974) Akole-ban (Mahārashtra) született, és Indore-ban nevelkedett, ahol apja, Shahmīr Khān a hercegi udvart szolgálta sārangi játékosként. A fiatal Amīr Ali már korán elkezdte az éneklést és a sārangi gyakorlását.

Az ifjú Amīr Ali képzéséhez apja egyszer a merukhand szisztéma dokumentációját kérte az indore-i udvar egyik kollégájától, Ustād Nasīruddin Dāgar-tól. Az Ustād ezt azzal az indokkal utasította el, hogy “egy egyszerű sārangi játékos fia” számára ilyen tudás nem áll rendelkezésre. Ez a megjegyzés megbotránkoztatta Shahmīr Khān-t, és saját módszert dolgozott ki Amīr Ali merukhand-oktatására.

A merukhand diszciplína (meru = hegy, khand = töredék) a hét hangból létrehozható 5040 (7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1) dallamminta logikusan egymásra épülő kompendiuma. A minták egy bizonyos logika szerint vannak szekvenálva, és végtelenül sokat kell gyakorolni őket, amíg “be nem programozódnak” a zenész gondolkodási folyamatába. E minták elsajátítása nyilvánvalóan a zenész technikai képességeit is fejlesztette, hogy a legbonyolultabb dallamszakaszokat is képes legyen végrehajtani. Egy rāga előadásakor a zenész a rāga nyelvtanával összeegyeztethető mintákat választ a rāga dallami személyiségének felfedezéséhez. (Shrī Dīpak Rāja)

Az Indore gharānā előadásai Abdul Wahid Khān stílusával és a Rājab Ali Khān-ra emlékeztető tāna-akkal tűnnek ki. A merukhand struktúra hasonló a Bhendibazār gharānā Aman Ali Khān által gyakorolt szerkezetéhez. A khyāl gāyaki az Indore gharānā-ban megtartja azt a lassú fejlődését és a sallangoktól való tartózkodását, mint a késöbbi Amīr Khān zenéje amely introvertált, méltóságteljes “darbār” dhrūpad stílus volt.

01= Indore Binkāri bāj

Alapító:

Bande Ali Khān Indore Bīnkār Gharānā (1830 – 1896) a saharānpur-i Ghulām Zakīr Khān fia, a Sādiq Ali Khān of Jaipur kortársa (1893 -1964).

Nővére Behrām Khān Dāgar felesége volt.

Tanítványa Abdul Wahid Khān of Kirānā volt.

02= Mewāti Gharānā

Ghagge Nazīr Khān és Wahid Khān a Mewāti gharānā kútfőinek számítanak. Eredetileg Qawwal Bacchon gharānā leszármazottai.

Raīs Khān (1939 – 2017) eredetileg a Mewāti gharānā-ba született, amely azonban az Indore gharānā-hoz és a rūdra-vīnā technikával kombinált “binkār bāj gāyaki ang“-hoz kapcsolódik, amelyet Raīs Khān apja, Mohammed Khān, rūdra-vīnā és sitār játékos fejlesztett ki. A Mewāti gharānā-hoz tartozik, amely a Mogul korszakra nyúlik vissza, és híres énekeseket hozott létre mit pld, Hassu Khān (meghalt 1859-ben) és Haddu Khān (meghalt 1875-ben) mindketten a Bāde Inyat Hussain Khān (1837-1923) iskolájából.” (Ő volt az első, aki bevezette a késöbb elterjedt bol-bant technikát a Khyāl Gāyaki-ban.

03 = Etawah Gāyaki Ang

Sarojān Singh ebből a gharānā-ból a Delhi-ben lévő Mughal Darbār alkalmazott énekese volt. Fia, Turab Khān (korábbi nevén Baddu Singh) és nagyfia, Sahabdād Khān (korábbi nevén Saheb Singh) szintén a senia-i Nirmāl Shah Bīnkār shagīrd-je volt, egyben Sahabdād Khān, a Gwālior gharānā nagy énekesének, Ustād Haddu Khān-nak a sógora volt, és tőle tanult éneket is. Kezdetben mint énekes és sārangi játékosként müködött. De később elkezdett sitār-on is játszani, és ő lett a surbahār nevű hangszer kialakítója is.

Az Agra melletti Etawah-ban élt (innen kapta a gharānā a nevét), ahol a Naugaon Darbār zenésze volt. Két fia született, az idősebb Imdād Khān (1858-1920) és a fiatalabb Karimdād Khān.

Imdād Khān vérségi és tanitványi láncolata: Enayat Khān (1894-1938), Vilāyat Khan (1927-2004) és családjuk, Wahid Khān ( ?), Shāhid Parvez (1954-), Budhaditya Mukherjī (1955), stb.

Seniā – Maihar Gharānā

A gharanā-hoz tartozó zenészek követik a legszigorúbban egy tradicionális dhrūpad rāga ālāp-jhōr-jhāllā részeinek előadását. Ezek a tételek mindig ritmuskiséret nélkül vannak előadva. A jhōr előadása során a tempóváltozásokat használják a tételek elválasztására, és egy rövid ritmikus figura jelzi a szakasz lezárását, tehát a jhōr-on belüli ritmusfigurák szerkezeti jelentőséggel bírnak. Ez a frázis-záró motívum minden nem Seniā jhōr előadásban is felbukkan. Előfordul, hogy az ālāp-jhōr tételeket általában egy khyāl stílusú vilambit gat követi tāna improvizációkkal, és az előadás egy tāla periodusban előadott jhāllā struktúrával zárul.

Az 1930-as évek közepétől Maihar-ban (U.P) történik meg az Ustād Allāuddin Khān által képviselt és az akkori Indián belül egy speciális zenei stílus – a Bīnkāri Bāj – kialakulása, amely – bár az 14oo-as évek mogul udvari zenéje, a Seniā gharānā a forrása – az eredendően vokális indiai zenei óceánon belül, egy kicsiny és a nagymúltú hindusthān-i zenére egyáltalán nem jellemző absztrakt instrumentális stílust képvisel.

A stílus jellemzője tehát a ritmikai-matematikai konstrukciók évszázados szabványosításából származó (matrix) készletek – fehér ember által könnyebben majmolható – kódrendszere, a dallamvariációk és azok modális poliritmiáinak szegényessége és hűvős – az utódok előadásaiban olykor sivár – távolsága az énekelhetőség humán-eksztatikus faktorától.

Szemben a merukhand-i koncepcióval, ahol a az elkülönült rāga skálák kidolgozott (aroha – avāroha) piramisszerű matrix épitkezései és a vérré vált improvizációs tāna-sargam-bol-bant asszociációs készletek a mindenkori rāga-k hangsorából következő legjellemzőbb karakterre (rasa) koncentrálnak, addig a Seniā-Maihar szisztéma akár több száz felhalmozott és kigyakorolt ritmikai patternek ráültetését végzi a rāga-k hangsoraira.

Ustād Abdul Wahid Khān (1871–1949) ezért gyakorolt életében mindösszesen két db rāga-n, míg például Pt. Ravi Shankar közel 100 darabot vett lemezre.

(Abdul Wahid Khān nap mint nap a Todī-t és Darbāri-t gyakorolta (riyāz). Amikor megkérdezték tőle, miért korlátozta magát csak két rāga -ra, azt válaszolta, hogy a másodikat is elhagyta volna, ha a reggel örökké tartana. Szerinte egy élet nem volt elég ahhoz, hogy igazságot tegyen bármelyik rāga között. Csak a lenyugvó nap és a gyülekező sötétség miatt volt kénytelen a Todī-ról valami másra váltani.)

A Seniā gharānā eredete a mogul udvari zene azon Akbār Császár fénykorából származik, amikor is az első instumentális kompozíciók a korabeli vokális műformák sokaságait másolták hangszereiken (rūdra-bīn, surshringār, sarod, rebāb, etc).

Így történik meg, hogy az eredetileg hangszerszerűen énekelt klasszikus zene mint énekelhetetlen absztrakt instrumentális stílus jelenik meg a középkori hindusthān-i vokális zene tengerében.

A Seniā gharānā legismertebb képviselője Pt. Ravi Shankar (1920-2012) révén történik meg a fehér ember utolsó találkozása az észak-indiai zenével, amikor is az 5o-es évek második felétől az indiai zene egészét és eredetét illetően eme kisebbségi, bár előadójában zseniális szeletével azonosították a történelmi és a létező indiai zenét, kezdve John Cage-től Yehudi Menuhin-on át egésze Beatles-ig.

Napjainkban:

Elképesztő homogenitás, minden beérkező pigmentgazdag irányzat villámgyorsan lehülyül a dúr-moll szisztéma jazzoid-gershwin-i hangzásvilágára, beleértve a repetitív (minimal) school nagyrészét is. A jazz öncélú, sehova nem vezető onániáját összekeverték a keleti zenék évszázados improvizációs gyakorlatával, holott ég és föld a kettő. Ez a borzalmas és torz gyakorlat ma tovább terjed, egyre rémisztőbb mennyiségű giccshekatombákkal.

Ez a jelenkori elképesztő zenetörténeti csőd jól látható az agyonhypolt Whiplash (2014) cimű, kultúra, zene és ember ellenes filmben, ahol az amerikai brutalitású „esztétikai” diktatúra öklének humanizmusa ráradializál a halandók kiszikkadt nyúltagyára, tehát ahol a másodpercenként onanizált hangok mennyisége legitimálja a zenei tehetséget.

*

Miután egy tradició részeseként létezni csak beleszületéssel lehet ez egyben azt is jelenti, hogy onnan kilépni soha nem is lehetséges. A felbomló társadalmi szövet elveszíti kultúrális kohéziós erejét és ezért a korábban zárt iskolákba beleszületett családi genealógiák féltékenyen örzött intellektuális trezorjai, technikai titkai és öröksége mint családi cimerpajzsok élnek tovább. Jelentőségük azonban a zenei örökség továbbadásában csökken és az úgynevezett zeneipari piac genre szabványaiba homogenizálódik.

Nagyon szomorú látni, hogy ebben a végső Sonderangebot során a nagy Ustād-ok és Pandit-ok, akik megengedhették volna maguknak, hogy ragaszkodjanak egyedülálló, de halványuló családi hagyományaikhoz, a nyál lovagjaivá és a globális zeneipar manipulált ízlésének kiszolgálóivá válnak.

*

Ennek tudatában fel sem merült bennem, hogy kivülállóként majmoljam ezeket a hagyományokat, hanem megpróbáltam annak a barokk zenének az Európában kihalt köznyelvi gyakorlatát ötvözni a világ úgynevezett Keleti hemiszféráján még nyomokban létező lokális zenei köznyelvek gyakorlatával egyesíteni.

Mindezek feltétele azon ismeretek birtoklása amely lehetővé teszi a Föld zenekultúrájában egykor kisebbségben lévő és temperált öszhangzatai világszabványát globalizáló európai rendszer ötvözését az eltünőfélben lévő ázsiai zenei gondolkodás egyedülálló hagyományaival.

Az utolsó élő (ámde haldokló) köznyelvi zenei nyelv már csak az arab-indiai világban található meg ezen a bolygón.

A mahārāja udvarok eltűnésével (1947 után) párhuzamosan már megkezdődött a hagyományos indiai iskolák (gharānā-k) kihalása és a klasszikus indiai zene általános félreértése a “fehér ember” fogyasztása révén, egy olyan konzum indiai zene kialakulásához is vezetett, amely csak a szörnyűséges pop-new age ipar globális “konform-idiomatizmusával” volt összemérhető és végül kimondható, hogy az eredeti forrása a klasszikus zenének körülbelül Ustād Vilāyat Khān szimbolikus halálának napján ( 2004. március 13.) kihalt.

Ma már a tāntrikus végbéltisztítás és a 4/4-es minta-loop-okra hülyített szórakoztatóipar zenéje jellemzi a világzene giccsvilág és a wellness-ambient műfaját, amely globálisan a Wychi-Exonybm Corporation egyik Wellness-Neuronetics alosztályaként fog működni.

(Hortobāgyi Lāszlō-Hortator, 2013)

CD GrFx Download

Trax Audition:

https://amarxe.bandcamp.com/album/sit-r-ang-i-ii-1982-2013-re-mix-mastered-version-series-vol-12